Thu Aug 28, 2014

How much do you really know about your ancestors? Were they good or evil? What traits were handed down through generations until they were bestowed upon you - the unique individual reading these words now? This is a question that has piqued the curiosity of many amateur historians and custodians of the family tree. Even if your ancestors made it into the history books, these so-called historical facts are often biased and skewed toward a particular cultural worldview.

I wonder if this problem will be mitigated with the rise of our wonderful internet age, where 100 years from now, your descendants could read your blog posts and get a very real sense of who their ancestors were. Will Facebook profiles still be around 100 years from now? Will your Great Great Great Grandchildren be aghast when they discover your favourite singer was Katy Perry? All intriguing questions indeed.

Well, ironically, it was through a family Facebook group that I was introduced to some of my ancestry. Granted, the further back you go, the larger the family tree becomes until the roots of your existence spread so far and wide, it is all but impossible to get a clear picture of your entire background. But in this blog post, I’d like to talk about my Great Great Grandfather, Charles William Pearce (C.W. Pearce for short). He was a Baptist missionary and the first in my mother’s family line to move to South Africa (my own father immigrated to South Africa as a young lad of 15. And, I of course was raised in South Africa and immigrated to Canada in 1997. But I’m getting ahead of myself).

C.W.Pearce did end up in the history books, as missionaries had to submit field reports as part of the public church record. I’ll be quoting from there as well as inserting information gleaned from living relatives and various family documents. There is a surprising amount of information out there on him.

Let’s go back 142 years to the year 1872, when Charles was born to proud parents William and Ellen Pearce in Footscray, Australia, a suburb of Melbourne. William Pearce was originally from Portland, England, having left for unknown reasons. He travelled to Australia on a steamboat - a long, arduous journey in those times, but not for William - who found love at sea. He met an orphan on the steamer and promptly married her. The orphan, Ellen Smith, was on her way to be adopted by a rich uncle. Once the uncle heard of the marriage, he was outraged and disowned her. Anyway, William Pearce (who is my Great Great Great Grandfather) became a strict Methodist lay preacher and eventually died in the early 1900s from a lung disease common to quarrymen. William and Ellen had four daughters in addition to Charles.

When Charles was born, his father prayed that the new-born child might grow up to be a messenger of God “to those who sit in darkness and the shadow of death.” As the story goes, his prayers were answered as Charles grew up so strong in the faith he decided to become a missionary. He put aside his apprenticeship as a gardener and florist and became a missionary student at Angus College in Melbourne. At the age of 22 he headed off to Africa, with no idea of what awaited him there. His mother, Ellen, would miss him dearly and in later years sent him heartfelt hand-written poems about her blessed and only son. He only returned once to Australia, in 1910 to visit his mother and sister.

So it was in 1894, my Great Great Grandfather, C.W. Pearce moved from Australia to South Africa, and in 1895 was appointed to the Tshabo Mission in what is now known as Kwazulu-Natal to take up missionary work.

Apparently my Great Great Grandfather was a natural with languages. At the end of 1895, he was the fourth missionary to arrive, and “arrangements were made for him to reside up country that he might become acquainted with the language and customs of the Kafir.” A natural linguist, he was preaching in Xhosa within six months of his arrival, despite making some “queer mistakes” at first. Within a few years of his arrival, he met and married a Miss Webb. Their marriage eventually produced seven children, despite Charles often putting his work before his family. In his zeal for evangelism, he would take long journeys by train and horseback to other areas of the country.

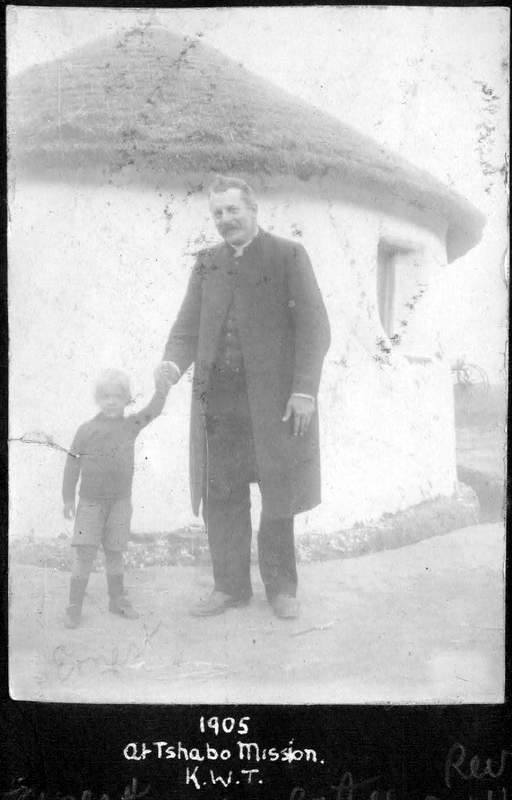

Here is a picture of him at the age of 33:

The young boy in the picture is my Great Grandfather, Ernest Pearce, who was born at the Tshabo Mission. He learned to speak Xhosa even before learning English. In later years, my Great Grandpa Ernie was reluctant to show this picture to his family because he had wet his pants. Apparently he had difficulty with his potty training. And now I present this embarrassing picture to you, the Internet. Please forgive me Great Grandpa.

Now, back to Ernie’s dad and my Great Great Grandpa, C.W. Pearce.

Let’s be honest, the history books aren’t exactly kind to missionaries in the colonial era. And rightly so, in most respects. In retrospect, the global implications of forcing white man’s culture on indigenous populations hasn’t been an overwhelmingly positive experience. But I’m not about to judge the motives of any one man embedded in the cultural and historical milieu of the time. I just want to subjectively tell you what little I know of my Great Great Grandpa’s story.

As he set about converting the “natives” to Christianity, C.W.Pearce ran into many cultural difficulties, as well as roadblocks from the inherent racism in the church. For instance, one of the keys to missionary work was training local evangelists to go out into the field and spread the word amongst the people. Unfortunately, salaries were racially determined and Europeans were paid far more than locals. According to the budget at the time, C.W. Pearce was making £112 a quarter while the “native” evangelist was only making £5.

My Great Great Grandfather pushed to develop more education for evangelists through a formal training centre, but could never drum up enough support from overseas. The result was that some evangelists strayed from church doctrines into alternative beliefs born from racial tension. For instance, in a 1906 field report, C.W. Pearce describes the secession of Mr Nacapayi:

…Ncapayi, who, as those who are acquainted with the Tshabo work will remember, was a foremost worker until he was drawn away by a ‘wind of doctrine, by the sleight of men, and cunning craftiness’ which masked itself under the monstrous contention that Baptism if administered by white men was no baptisim at all. It is a matter of great regret that some of the best succumb to the strangest ideas, which are disseminated by ignorant, unbalanced or wicked men. The only effective antidote is the stability which comes from fuller knowledge and discipline; and everyone who comes into touch with the practical work of our Missionary Society has continually brought home to him the conviction that one of the absolute necessary auxiliaries to our work is a Training Institution for our Native Workers.

Furthermore, better economic opportunities in colonial South Africa could be found in the gold mines. C.W. Pearce’s words from a 1911 field report:

We have great difficulty to supply the preaching services at the outstations, for no less than nine of my deacons and preachers have been recruited for the mines in Johannesburg and German West Africa. It is a pity that we have no organised native work for our Church at Johannesburg, and the sooner we have a Baptist cause for the natives in that centre the better it will be for our work.

But one area where he saw great success was in the founding of a local school. In fact, by 1914, the school was bursting at the seams. C.W. Pearce reports:

Owing to the increase of attendances at the school in Tshabo from 27 scholars to 131, it has been found necessary to enlarge the accommodation, by taking down the wood an iron church, and building it on to the old disused stone building.

According to a church report at the time, “the increased attendance was due to the adoption by the Natives of the Location - Christian and heathen - of the principle of a voluntary tax for elementary education of their children.” In the same field report, Rev Pearce proposed “the raising of a Building Fund for Native Churches, to be loaned to the Churches and paid back by monies at the opening service. In his opinion, “a modest capital of 100 pounds or so would be of great service.”

A second school was opened, and C.W. Pearce was given a whole week off to kickstart it. From a church report:

In the interim, this Assembly feels is is necessary to ask the Missionary Committee to set Rev. C.W. Pearce free from his present work, for at least a week to enable him with Mr. H.G. Meier, to try and bring matters to a better issue at Tshabo….

By 1919, C.W. Pearce was the superintendent of 12 Sunday schools, 20 teachers, and 240 scholars. But despite his success, my Great Great Grandfather was somewhat disappointed by the quality of the education. In his 1919 report, he reported that the schools “are of a primary character and instruction given is quite elementary and not all we would desire. This was because “with the exception of the Bible and a hymn book compiled by another denomination we have no literature in the Kaffir language suitable for this work.”

Amusingly, to solve this problem, the church asked superintendents to introduce the Baptist magazine Wonderland into their Sunday Schools, and that “a letter be sent periodically from one or other of our Missionaries to our European young people as an insert.” So basically, ESL classes haven’t changed much in the last 100 years!

Also of disappointment to Rev Pearce was the reluctance of the local people to give up their cultural practices. In his 1919 field report, he states:

During the year a new Sunday School was opened at Lower Tshabo with two teachers and 21 scholars, [unfortunately] some of them [were] still in their red blankets. This are the same type of attire about which Pape was so disgusted that the natives are attending church services in their raw heathenish costumes.

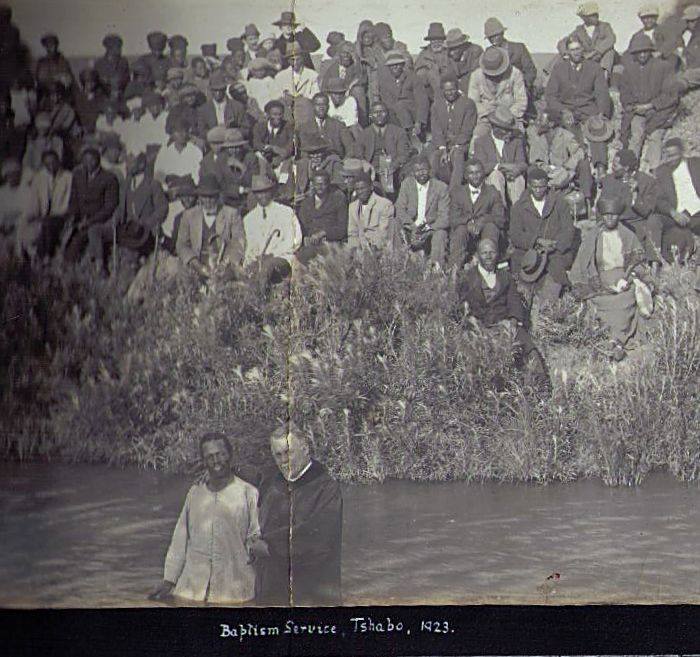

By 1923, my Great Great Grandfather baptized a lot of people (he baptized 200 in his first two years alone, so who knows how many in his lifetime). Here is a picture of him doing exactly that:

After 33 years of service, he was instrumental in establishing more than 100 churches.

On 1pm on the 29th December, 1926, Rev Pearce died of a sudden heart attack. It is said that he had just laid down his pen as he finished writing notes for his last sermon. Three quarters of the way down, he wrote just these words: “The wonder of sudden death.”

When reading field reports, biographical sketches and obituaries, it is almost impossible to garner the internal motivations of any person. But they say that the true worth of a person is defined by their actions. I think it is telling that, and he never mentions this in his field reports, every Sunday he would visit the local prison and not only give a church service, but listen and talk with prisoners from all walks of life. Indeed, he was a man of such ambition that he was frustrated by the limits imposed by the church administration. In a 1927 biography in The South African Baptist magazine, the biographer writes this of Rev Pearce:

His zeal for the spread of the gospel and the ingathering of the native peoples was a frequent cause of embarrassment to the Missionary Committee, who were constantly being faced with the problem of how to keep pace with his widespread activities on their slender resources.

In 1927, the church handed over control of the church to the locals and the “Bantu Baptist Church” was founded. An honorary mention is given to C.W. Pearce’s wife in a description of the inauguration of the new church administration:

Another meeting was organized for all the Superintendent Missionaries of our various fields. This occasion was convened purposely at Kingwilliamstown, so that a day could be spared from its business and devoted to the inaugural ceremonies. On this occasion, a fleet of motor cars took the missionaries out early [to Tshabo]. Also part of the gathering was the widow of our late Kaffrarian Superintendent, Mrs C. W. Pearce, who was also of the party.

In 1932, a collection of his Xhosa hymns was posthumously published and are still sung in the Baptist church today.